Venture capital would make a great board game. There are huge highs and lows. There are tough decisions to make and you must plan long-term. It’s competitive. And you would get to handle lots of play money.

A board game would also be a great teaching tool. There are countless books and blog posts about VC funding but founders still feel confused. I recently surveyed 75 early-stage founders and 88% said they were “extremely interested” in understanding how VC worked.

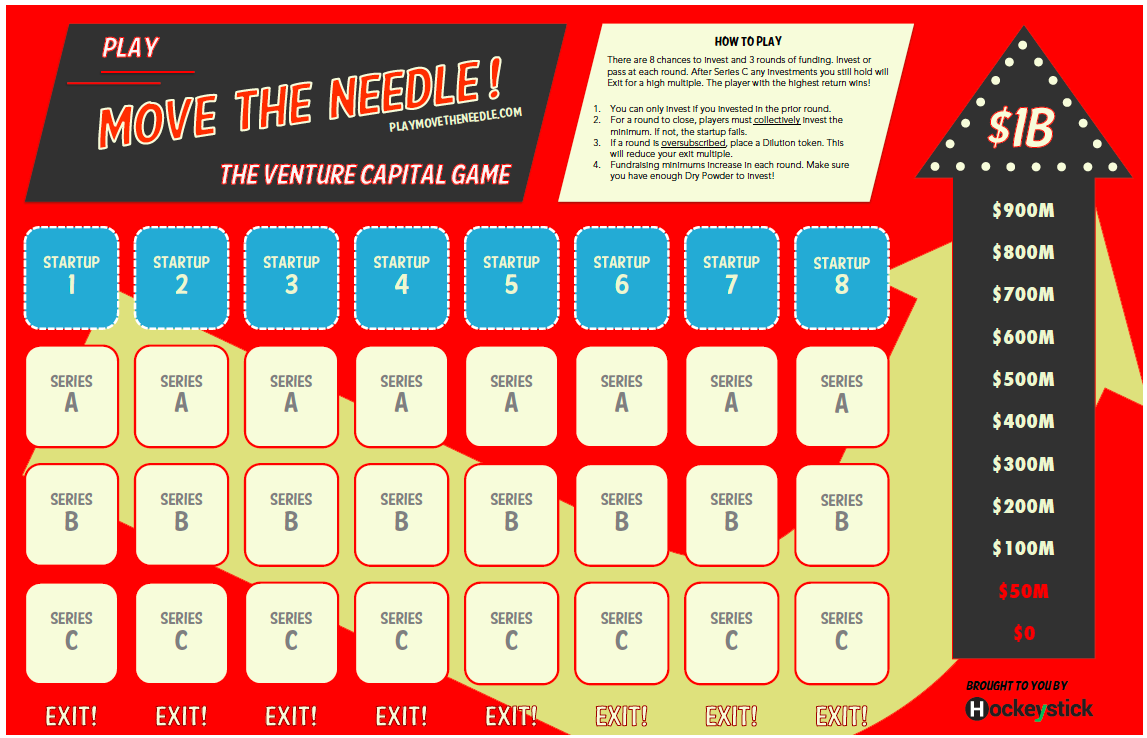

Back in 2015 I created a game concept called Move the Needle. This is what the game board looked like:

The game involved building a portfolio of 8 startups and supporting (or dropping) them over three rounds of funding to an exit. The fund with the highest return won.

I wanted to create a fun activity to run at startup events and I playtested it at the Atlantic Venture Forum and StartupFest. I learned three things:

- It was too complicated, took too long to explain, and involved way too many little game pieces. Too much time was wasted explaining the rules.

- Players wanted to feel like they were building their own portfolio, not just saying yes or no to startups 1-8.

- Play money blows away in the wind (StartupFest is outdoors).

In 2023 I still think a venture capital game would be fun and I still think founders would gain a lot of insight about how VC works by playing.

So let’s go through the process of designing a venture capital game.

Thanks for reading A Leap of Faith. Subscribe for articles on pitching, funding and founder storytelling.

Learning Goals

It would be easy to make a game where you randomly pick companies and roll dice to make investments (not a comment about any specific VC’s fund thesis). But I want this game to be educational as well as fun.

The game should be fun for anyone but targeted at entrepreneurs. I think players should leave with a better understanding of these concepts:

- The difficulty of picking winners (if you’re a VC reading this add “for others”)

- Allocating capital for new vs follow-on funding

- Why dealflow is important

- The impact of what stage you invest

- Different types of return: absolute dollar, multiples, IRR

- The role of time in venture capital

- Power law curves of fund returns

- How uncertainty affects portfolio construction

- Competing with other fund managers

You could do that in a lecture but I think founders will develop a better understanding of venture if they put themselves in a fund manager’s shoes.

I don’t want to model cap tables. That would be too complicated and not fun. I don’t want to make a game called TVPI and play it in Excel.

Gameplay Goals

The most difficult goal to achieve is to make this fun. Like interpretive dance, fun is difficult to describe but easy to recognize.

My goals for fun gameplay include:

- The feeling of investing in a company should be like buying Park Place in Monopoly

- Being able to execute a fund strategy specific to how you want to play, eg early vs late, focused vs spray and pray

- Having to make difficult choices to re-invest or pass

- Visually tracking your portfolio

- Competing to get into a deal or convincing others to co-invest

And handling play money of course.

Other Requirements

- I want this playable by a large range of players (1-100) so it can be played at home, a workshop, or a conference

- There should be ways to customize the game for different playstyles and learning goals

- Learning from past mistakes, there should not be too many fussy pieces

Design challenges

How to visualize a VC portfolio

I kept coming back to having a printed game board as the best way to visualize and track a portfolio. Like the original Move the Needle game. But this had drawbacks.

A printed board means you have to cap the number of companies in a portfolio. And cap the number of funding rounds. You need game pieces to track which startup you invested in, which round and how much you invested. The board needed to be big and you needed one per player.

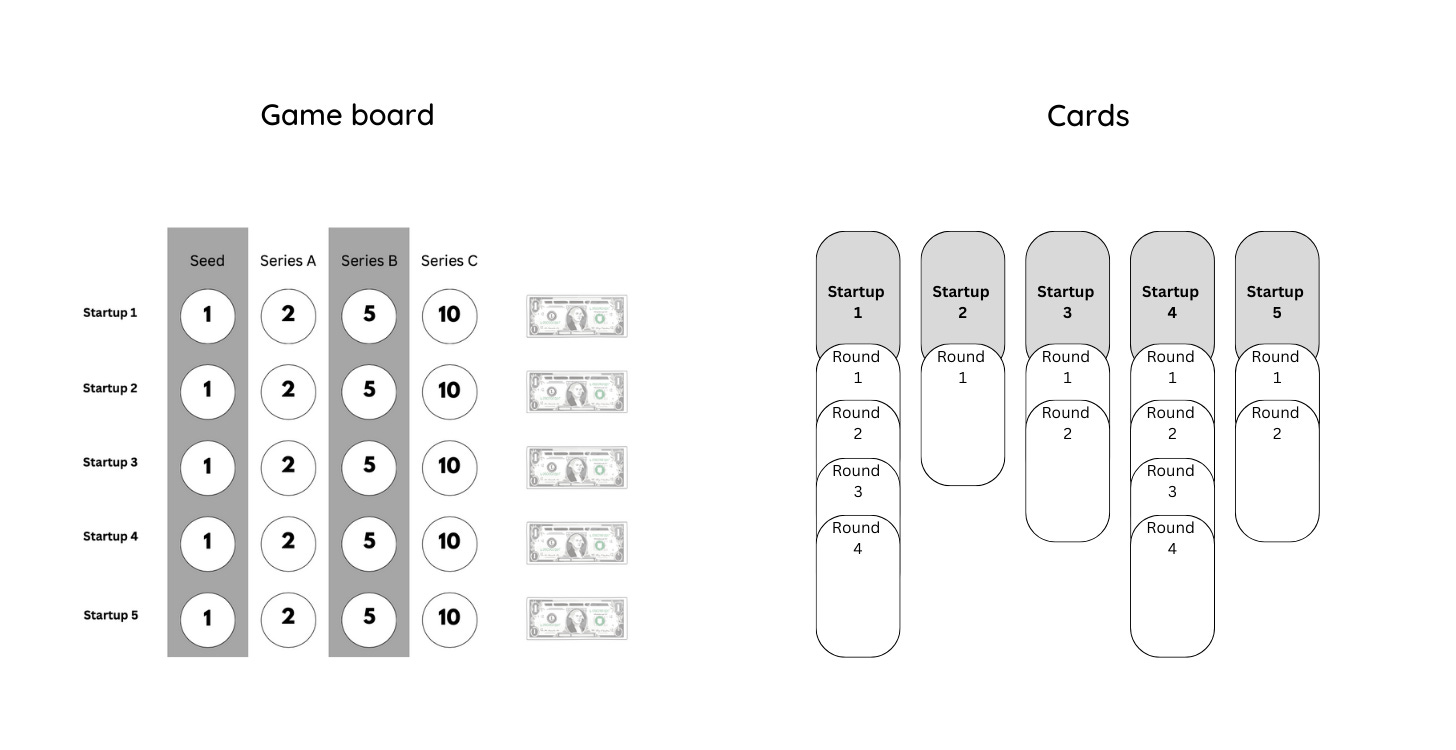

After fiddling with different layouts I realized that doing everything with cards was the answer.

You build a portfolio like playing solitaire. A column is one company and you place funding rounds below. No limit to portfolio size or number of rounds. It saves space, does not require a printed board, and lets you add more types of cards into the game for different events. You can shuffle a deck of cards so there’s no need for dice.

How to Calculate Returns

Winning the game is about generating the highest returns. The game should show that exiting early generally means a lower value. But it should also show that in a later-stage exit, the earliest investors generally have the highest multiple.

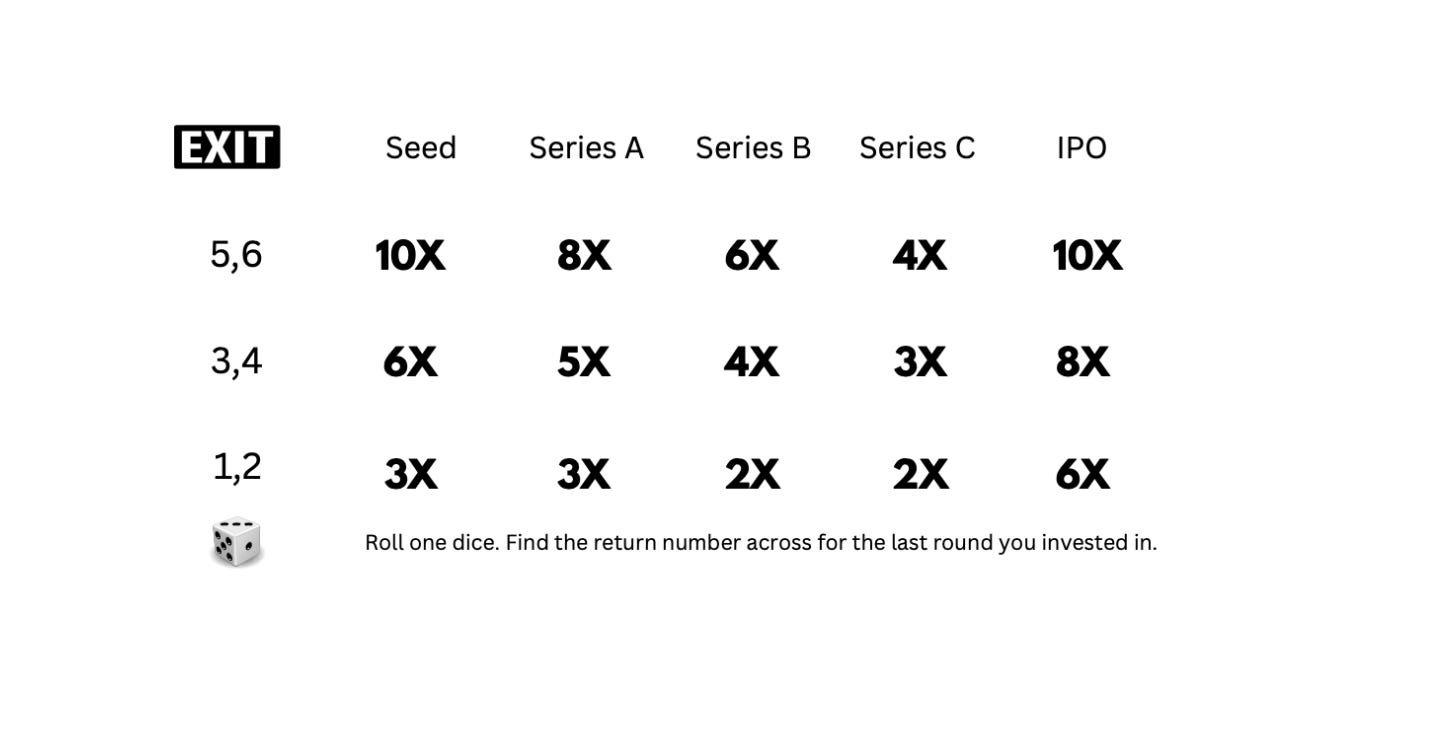

I went through different iterations of an exit scorecard like the one below:

This involved keeping track of what stage the company was at, e.g. Series B, then rolling a dice for low, med or high exit multiples. It was difficult to explain. Also, dice made it feel too random.

You can see there’s something strange about saying an exit at the Seed stage is 10x but one at Series C is 4x. It’s true for the amount invested at the Seed stage, but usually doesn’t apply for an early exit.

Again, cards came to the rescue. I decided I would print funding rounds and exit values per company. This meant I could eliminate the dice and exits table, which was confusing. Having the potential returns on each company’s card meant different cards now had different value depending on your fund strategy. Eg I could have companies requiring a lot of up-front capital but with a high payoff in the future. Or vice versa.

Saying there is a range of potential exit values for different types of companies is not unreasonable.

Competition

The part I am still developing is making sure the game is competitive. I think competing for a numerical return is probably not fun enough (or not as fun as it is in real life).

I’m working on finding a way to force players to compete to invest in a company. I’m thinking of limiting the number of companies (deals) presented every turn. Eg 10 deals for a game involving 5 players. Players would have to balance investing as soon as possible, which is better for fund returns, vs waiting for better dealflow later. If multiple funds want the same deal there could be a bidding war.

Another way to force more negotiation between players is to have some rounds require co-investors. Players who couldn’t convince another fund to invest would be penalized, eg the company could go bankrupt. This could be fun and educational if some players played late-stage funds who were forbidden from investing early.

What’s Next?

I wanted this post to be about overall design principles and some of the challenges in designing a venture capital board game. There is much more to talk about fund figuring out how much money to give each player to arguing about probabilities.

Between now and my next newsletter I’ll be playtesting a beta version of the game with 25 founders at my workshop, All Fundraising. No Bullsh*t. Next time I’ll share images of the actual game and more in-depth gameplay.

Leave me a comment or email me if you have ideas you think would make this game great.